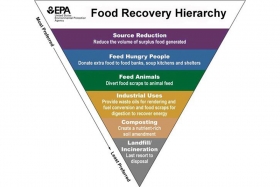

Reducing Food Waste in Foodservice

October 16, 2018 by Doreen Garelick, Dietetic Intern

Our intern Doreen attended a food waste summit for restaurants and compiled these tips to help food service operators redirect…

Nutrition 101

June 25, 2013

Dietetic Intern Tim Chin takes a look at the scientific theory that claims certain ingredient pairings are destined to end up together.

Growing up in the kitchen, I took certain things for granted and many things as gospel. Whisk for meringue. Cleaver for chicken. Cornstarch with water. Acid with baking soda. Bacon on everything.

Similar maxims also applied to combinations of flavors: onions and garlic, coffee and chocolate, tomatoes and mozzarella and soy sauce with ginger. To me – and to most – these pairings make sense. Our mothers, fathers, grandmothers and friends rely on these flavors to feed us – reinforcing our conviction in their palatability. Whether due to cultural reinforcement, genuine deliciousness or sheer happenstance, people have some idea of which foods work together.

In fact, compared to the some 1,000,000,000,000,000 (that’s a quadrillion) recipes possible given the number of food items available worldwide, one article I’ve read suggests that only 1 million recipes are in popular use today. And of the more than 50,000 recipes on popular North American websites, nearly 50% have some combination of garlic and onions.

But why do these flavor pairings work? Where do they come from? Can we predict new ones? And what are the implications for our health?

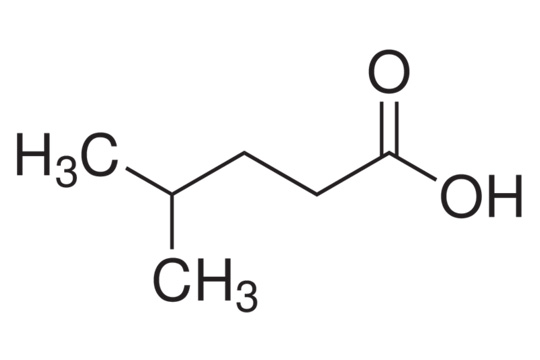

A quick investigation leads to the relatively new, under-researched area of flavor-‐ pairing theory. The concept is simple: foods that share flavor compounds are likely to go together. Moreover, this idea suggests that the more flavor compounds two foods share, the more likely they are to occur together in cooking. For instance, the classic pizza combination of tomatoes, mozzarella and Parmesan cheese all contain 4‐methylpentanoic acid, so they are said to be “logical” pairings.

On the other hand, this kind of model lends itself to unexpected and sometimes unsettling combinations: pork and jasmine, or better yet white chocolate and caviar. These pairings defy conventional sensibilities. But they are said to be complementary – even delicious and flavorful.

Such discoveries are the pride and joy of one Heston Blumenthal – the British, bespectacled chef, owner of three‐Michelin-starred restaurant The Fat Duck and representative of the ethos of his modernist cooking philosophy. For chefs of the so-‐called “modernist” modality, aspirations toward culinary perfection may align themselves more with science than intuition and personal experience.

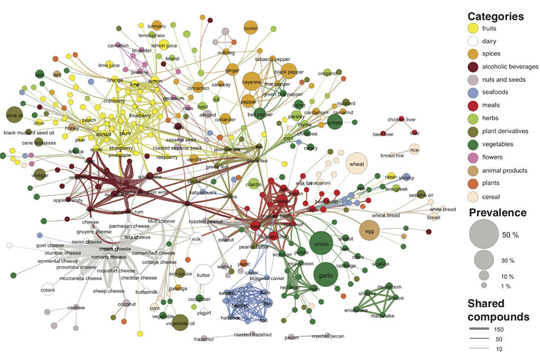

While it would be convenient to follow these scientific pairings to the letter, some are not convinced that it works. In December 2011, a group from Cambridge University developed a ‘flavor network’ pooled from over 50,000 recipes from North American, Western European, East Asian, and Latin American cuisines. Their work showed a curious difference: results suggested that North American recipes used significantly more compound-sharing pairs than would be predicted by chance. By contrast, East Asian recipes employed few to no compound-sharing pairs. So, the group concluded that flavor pairing is not necessarily a cross-cultural phenomenon in cooking.

The Flavor Network, in all its confounding glory. Photo credit: nature.com

Others believe that the flavor‐pairing paradigm still needs research. “The biggest problem in this field is really a lack of data,” says Martin Lersch, the Norwegian organometallic chemist behind the popular molecular gastronomy blog Khymos. Indeed, the cost of extensive flavor analysis – including professionally trained tasters – is prohibitive for most institutions. “It’s ridiculous,” says Harry J. Klee, a professor of horticultural science at University of Florida who has devoted years to studying volatile flavor compounds in the tomato. “That whole flavor-pairing crap is just a gimmick by a chef who is practicing biology without a license.”

In any case, the jury is out on flavor-pairing. What do you think? Do you tend to pair flavors when cooking? Do you think it’s a valid model?

Next time, we’ll take a look at flavor-pairing and any apparent nutritional synergies for health. Stay tuned!

Works Cited

Ahn, Yong-‐Yeol, Sebastian E. Ahnert, James P. Bagrow, and Albert-‐László Barabási. "Flavor Network and the Principles of Food Pairing." Scientific Reports 1 (2011)

October 16, 2018 by Doreen Garelick, Dietetic Intern

Our intern Doreen attended a food waste summit for restaurants and compiled these tips to help food service operators redirect food waste from landfills.

Nutrition 101

Nutrition 101

September 26, 2018 by Doreen Garelick, Dietetic Intern

Ever notice headlines about rapid weightloss? Dietetic Intern Doreen Garelick looks deeper into a recent eye-catching headline to see if there's any truth behind it.

Connect

Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter Friend us on Facebook

Friend us on Facebook Follow us on Pinterest

Follow us on Pinterest Follow us on Instagram

Follow us on Instagram Read our Blog

Read our Blog Watch videos on YouTube

Watch videos on YouTube Watch videos on Vimeo

Watch videos on Vimeo Connect with us on Linkedin

Connect with us on Linkedin Find us on Foursquare

Find us on Foursquare

Tweets by @SPEcertifiedBlog Search

Categories

SPE Certified Newsletter

Sign up for news on the latest SPE-certified venues, events and SPE updates.

We will never share your personal information with a third party.